The PlaceLab-er’s sat down with Professor Annette Markham to learn more about why she chose to utilise moodboarding, what you can do with the materials and what In The Mood is really all about.

Melbourne Moodboarding Workshop. Image: RMIT PlaceLab.

Why Moodboarding?

Annette: This project on “moodboarding” is the latest in a long line of arts-based interventions to make non-tangible forms of data more visible for citizens and policymakers alike. In the course of everyday life, so much of what it means to live in a place is invisible to the eye and ear because it is a sensation in the body or a feeling in the mind. Especially in these times, when data-driven technologies focus our attention on the numeric and quantifiable aspects of human actions and behaviours, it is vital to find ways to make sure we don’t fail to account for the rich, textural, non-quantifiable aspects of human experiences. Focusing on mood is a way of pushing back against the dehumanising tendencies of data analytics.

Why ‘moodboarding’ rather than some other activity to study affect in the city?

Annette: Moodboarding is a practice of arranging colours, shapes, and textures on a flat surface (board) to evoke or convey a particular feeling. It’s a form of visual layering that focuses our attention on how something feels rather than what it means. Moodboarding disrupts the logics of description and explanation. It is one of many forms of expression that seek to find and evoke affect – affect in this case referring to a pre-cognitive visceral sensation that happens just before we invoke some sort of cognitive logic and language to find a word to describe it to ourselves or someone else. Playing with arts and crafts supplies is a surprisingly easy and effective way to generate and then visualize some of these affective layers without thinking too much about it. By evoking mood in layers of texture and colour rather than words, we find a different type of material evidence of lived experience.

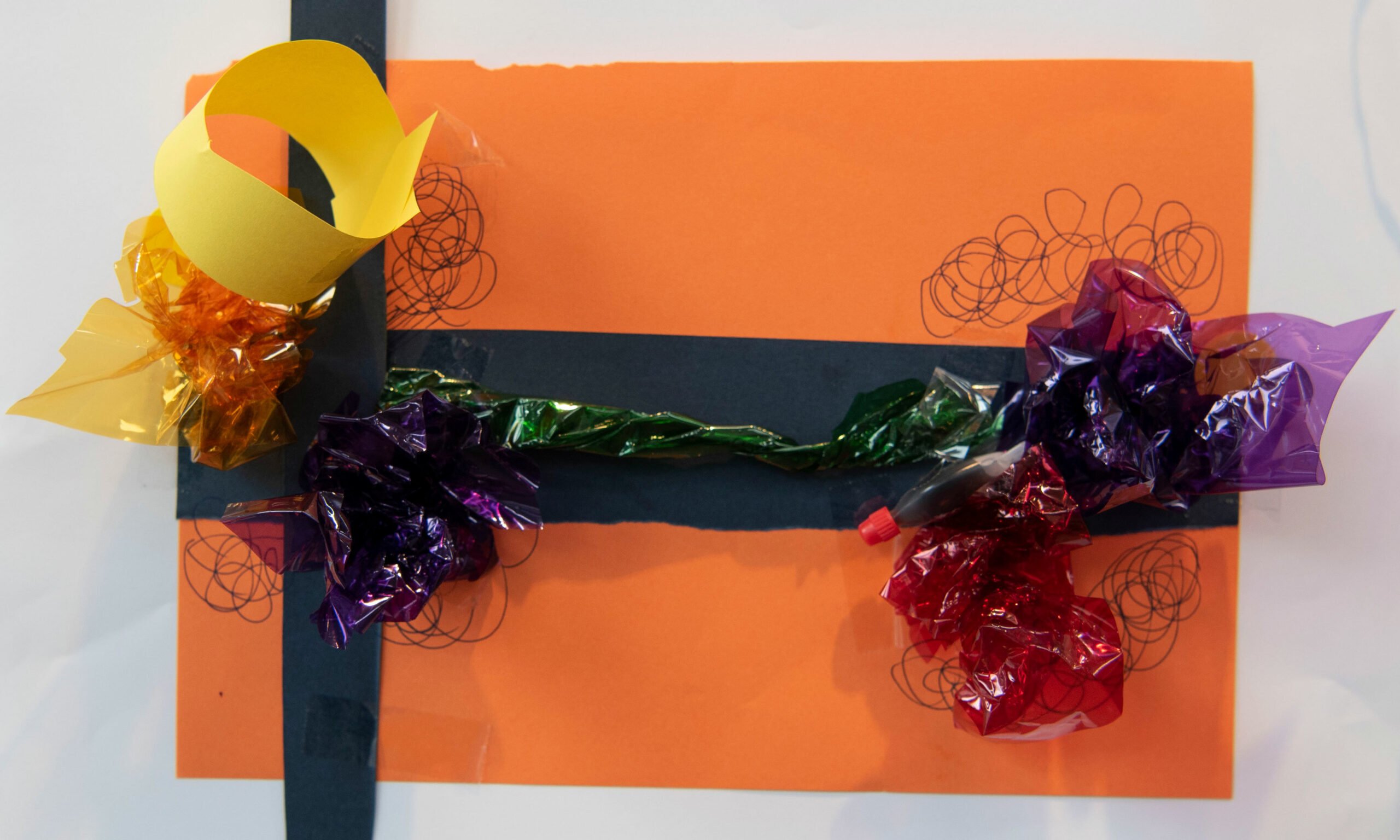

Moodboard from Melbourne’s Moodboarding Workshop. Image: RMIT PlaceLab.

What do you do with these materials?

Annette: For one thing, these experimental participatory workshops are for the participants themselves to explore the textural, sensory, and non-verbal ‘moods’ they’re feeling. But beyond the individual satisfaction of playfully generating these moodboards, people can work together to figure out what should or could be done with this material, or this affectively oriented way of knowing. Is this a valuable practice for people to explore what’s happening that is meaningful or disturbing to them and their communities? Is it evidence of some sort and how could it be added to the more quantitative forms of data that cities increasingly rely on for future city planning?

Thanks, Annette! We appreciate your insight into the In The Mood research project.